Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida was born in Valencia on 27th February 1863. His parents both died (probably from a cholera outbreak) when he was 2 years old after which he and his younger sister were brought up by their maternal uncle and aunt.

From an early age it was clear that Sorolla had a passion for art. The young Sorolla would spend much of his school days making drawings and by the age of 15 he was winning major prizes for his paintings at the Academy of Valencia.

Sorolla’s talent and hard work was brought to the attention of Antonia Garcia, a pioneer in photography based in Valencia.

In 1888, at the age of 25, Sorolla married Garcia’s daughter, Clotilde Garcia del Castillo. They had 3 children - Maria (1890), Joaquin (1892) and Elena (1895),

Portrait of Clotilde 1891

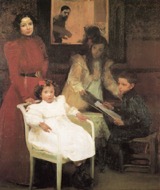

My Wife and my Children, 1897

My Family, 1901

My Children, 1904

By this time Sorolla was firmly established on the national stage and by 30 he had displayed paintings in salons and international exhibitions in Madrid, Paris, Venice, Munich, Berlin, and Chicago.

By the turn of the century Sorolla was recognised as one of the western world’s greatest living artists, receiving gold medals in several major international exhibitions.

Sad Inheritance 1899, winner of the Grand Prix and Medal of

Honour at both Paris and Madrid

The first decade of the 20th century seems to me to have been the happiest and most lucrative time of Sorolla’s life.

As well dropping the earth colours from his outdoor paintings and freeing up his brushwork during some wonderful summers in Javea and in other places along the coast near Valencia, his incredibly successful exhibitions and portrait commissions (costing up to $5000 for a full-length portrait) made him a very rich man.

Queen Victoria Eugenia, 1911

In 1912 Duncan Phillips Jr described meeting Sorolla a year earlier -

“I took the opportunity at Madrid last spring of visiting the painter in his new home. To my complete satisfaction he was just like his pictures. Whimsical, unconventional, jovial, kindly, the French would call him “Bon garcon”. It is a familiar type in the studio world. But how few of them have the genius of this little Spaniard!

“Sorolla was a charming host, putting my companions and myself at once at our ease by his almost boisterous familiarity, assuring us that although we were not painters, yet we were Americans, and therefore easy for him to like and understand. He spoke with enthusiasm of his friends in America, of his new commission to decorate the Hispanic Museum at New York with mural paintings, of his admiration for the American spirit, his belief that from us shall come the great art of the future.

“I drew him on to speak of his philosophy. He responded eagerly and with spontaneous eloquence. In answer to my remark that the distinguishing quality of his work seemed to be his responsiveness to the joyous influences of eth world - he exclaimed that art has no business dealing with anything that is either ugly or sad. He had painted one pathetic picture of crippled children bathing in the sea. Emphatically he would never paint another like it; there was too much of that sort of thing in life. “Is it any wonder,” he demanded, “that modern painters love the study of sunlight? Light is the life of everything it touches.” And again a little later, “La lumiere c’est la vie”. Therefore the more light in pictures the more life, and the more truth, and the more beauty. Children, flowers, sunshine - yes, those were the things he loved best.

“And when I praised the beauty of his house and garden, he smiled as if remembering former doubts and compunctions about the realisation of this expensive dream, and said very simply, “One can live only once. Let us be happy while we may.”

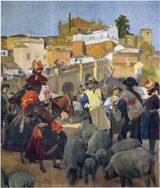

In 1912 Sorolla commenced the awe-inspiring “Vision of Spain” commission for the Hispanic Society of America through which Sorolla painted a series of massive panels depicting scenes representing the different regions and cultures of Spain. The canvases ended up measuring a total length of 227 ft and were up to 14ft high, sometimes requiring Sorolla to work off a ladder. The commission was finally completed in 1919.

Extremadura: The Market

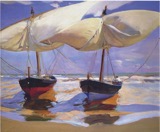

Whilst the Visions of Spain commission was clearly an incredibly feat and a fabulous historic record, I personally don’t get the same feeling of happiness and freedom radiating out of them as I do from his other works, with 2 exceptions - The Tuna Catch, Ayamonte and Elche, The Palm Grove, both painted in 1919. It is pleasing to note that that happiness stills seems to be present in the beach paintings he did during his breaks from the commission.

Beached Boats, 1915

Sorolla suffered a paralyzing stroke in 1920 and died three years later.